|

Abstract: The report concerns a married couple who were repeatedly invaded by pigeon fleas (Ceratophyllus columbae) over a period of 2 months. The source of the fleas was a pair of breeding feral pigeons (Columba livia). The birds' nest was located in the attic immediately above the couple's apartment, and the fleas found their way along an unsealed heating pipe. The people encountered up to 40 bites per night. With invasions repeated almost every night, the man gradually developed an allergic urticarial reaction. The most traumatic experience for the couple, however, was to learn that they were invaded by fleas (initially, they had presumed they were bothered by mosquitoes). This information resulted in severe psychological distress with phobic reactions and insomnia. Despite the successful removal of the fleas and the pigeons that were source of the pest, parasitophobia of the man persisted over the following 4 months. This case is discussed from the broader aspect of health risks related to feral pigeons and animal fleas. Also summarised are previous observations on people invaded by pigeon fleas. Key words: zoonoses, pigeon flea, Ceratophyllus columbae, human infestation, insect bites, allergic reactions, urticaria, parasitophobia, animal vectors, feral pigeons, Columba livia. |

Feral pigeons (street pigeons) pose a considerable health risk to the population. They are vectors of infectious diseases and a source of antigens causing allergic diseases. Breeding sites of the birds harbour parasites that may attack humans. The present article deals with the invasion of 2 persons by pigeon fleas (Ceratophyllus columbae) from a nest of feral pigeons.

Patients' history. A 34-year-old Swiss male (described here as Mr X) and his 30-year-old Ecuadorian wife (Mrs X) have lived for several years in the fourth floor of an old house in the centre of Lucerne (Switzerland). At the end of February 2004, Mr X noted on his hip two vesicular skin lesions of 1 mm diameter, surrounded by erythematous patches of approximately 1.5 cm diameter, which were apparently due to bites of an insect. Since then, almost every morning, he found 8-10 new bite marks on each leg, typically ordered in lines each of 3-4 marks. At the bite sites, red indurated itching papules developed, surrounded by erythema that would persist for up to 2 weeks. Gradually, urticarial reactions to the bites developed in the form of wheals of approximately 1 cm diameter, surrounded by erythema. The itching of the lesions became very distressing to the patient. Roughly a month after the first bites, a systemic urticarial reaction developed: the patient suffered from generalised pruritus, on his arms and legs urticarial wheals appeared, which were not preceded by fleabites in these areas. Additionally, the patient experienced intense itching at the sites of previous bites.

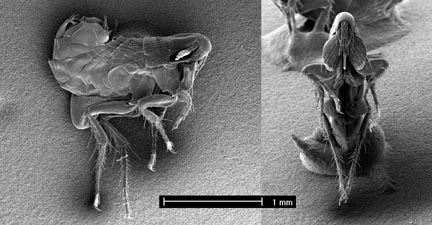

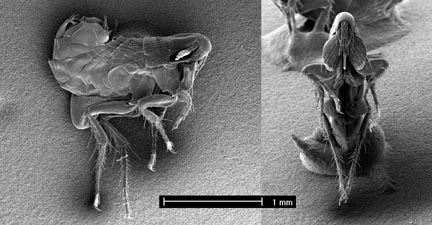

The medical history of Mrs X was very similar to that of her husband. The difference was that she suffered from more bites (up to 20 per night per leg), and larger vesicles (diameter 2-3 mm) emerged in reaction to the bites. Mrs X complained of intense itching that was triggered even by minor stimuli, like contact with clothes. The pruritus forced her to scratch vigorously, which finally led to widespread abrasions of the epidermis (excoriation). Initially, the couple presumed that they were bothered by mosquitoes. At the end of March 2004, Mr X caught some small insects that were subsequently classified by Dr Peter Herger of the Naturmuseum in Lucerne as pigeon fleas (Ceratophyllus columbae). The specimen was then sent for verification to the first author of this report, who confirmed the classification (Fig. 1). When the couple realised that they had been invaded by fleas, they became heavily stressed. They installed hammocks, hoping in this way to keep out of reach of the fleas. Despite this, they still could not sleep for days because they were too afraid of the fleabites. Mrs X developed a severe psychological distress and strongly insisted on changing their apartment.

On-site intervention was undertaken in order to help the couple to cope with their problem. They were living in a mansard apartment in a 200-year-old house. In the attic above their apartment, a pair of feral pigeons had been breeding for years. The pigeons' nest was located on the attic's floor that formed the mansard's ceiling (Fig. 2). A non-sealed heating tube led from the attic into the apartment; there were also several cracks in the masonry that would allow the passage of the fleas. We recommended Mr X to remove the pigeon nest, spray the site with an insecticide, and obstruct the birds' access to the attic. Additionally, we recommended the extermination of the fleas in the apartment by a pest control professional.

Figure 1. The pigeon flea (Ceratophyllus columbae) - lateral and anterior view (SEM, 15 kV, original magnification 75 x).

Figure 2. A single nest of feral pigeons (Columba livia) in the attic as a source of pigeon fleas infesting people living in the apartment underneath.

Follow-up. Four months after the first symptoms, we contacted Mr X again to learn about the outcome of the intervention. The roof had been repaired and sealed to prevent the feral pigeons from returning, and pest control had also been carried out. The couple had not sought medical advice in the meantime. Skin changes of Mrs X had been resolved completely; she also was rid of the anxiety caused by the flea invasion. Mr X, however, complained of still persisting skin problems: These were reddish spots of 4-5 mm in diameter at the sites of previous bites, which were slightly painful when rubbed. In contrast to the rather minor skin symptoms, he was still suffering from a strong phobic reaction. He complained of continuous anxiety and the feeling of living under a serious threat. We encouraged him to seek psychological help for his phobia.

Feral pigeons are distributed worldwide and live close to the human population, causing serious health problems. They may carry as many as 60 human pathogens - viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa [20, 38, 42]. Antigens of pigeon feathers and droppings may cause allergic respiratory diseases. Allergic alveolitis (syn. hypersensitivity pneumonitis, "pigeon breeder's lung") can be found in 1-10% of pigeon breeders [8, 12]. The prevalence of the disease in the general population remains unknown; however, pigeon allergens were detected in human dwellings, schools and hospitals [3, 10]. Nine cases of allergic alveolitis related undoubtedly to feral pigeons were reported in recent years (reviewed in [19]), one of which was deadly [34]. More are to be expected as the awareness of the problem increases.

In addition to the above-mentioned health risks, feral pigeons host numerous parasites. These parasites can attack humans, causing distress and occasionally transmitting infectious diseases. There are many reports on human invasions by the pigeon tick Argas reflexus [26, 28, 39], its relatives Argas polonicus [6, 35, 36] and Argas latus [14], and the red blood mite Dermanyssus gallinae [11, 16, 44, 47]. There are also reports on human invasions by the northern fowl mite Ornithonyssus sylviarum [44] and the bed bug Cimex lectularius [15].

Despite the pigeon flea (Ceratophyllus columbae) being a frequent ectoparasite of feral pigeons [18, 27, 37, 40, 48], we are aware of only 5 previous, partly anecdotal reports on human invasions. In 1961, pigeon fleas infested workers repairing the roof of a building populated by feral pigeons in Hamburg, Germany [48]. Two further cases were observed in 1962 and 1964, in dwellings in Leipzig, Germany, with pigeon nests as putative sources of the infestations [45]. In 1978, feral pigeons were repelled from the loft of the Natural History Museum of Basel, Switzerland. Some days after the closure of the loft, pigeon fleas attacked museum employees who worked in a neighbouring preparatory room [17]. In a further, unpublished observation, a nest of feral pigeons was removed from the attic of a house. One year later, pigeon fleas invaded a woman living in the mansard apartment below (Marcus Schmidt, Zurich, personal communication). Unfortunately, all these reports lack information on the health effect of the invasions.

Typically, animal fleas invade humans when devoid of their specific host [5]. The couple described here, however, was attacked while the pigeons were still present on-site. It is possible that the favourable temperature provided by the heating tube had promoted propagation of the insects to such extent that the nesting pigeons became insufficient as the feed source, which had driven the fleas to seek a new host. In fact, the host specificity of fleas is not as strict as with many other arthropod ectoparasites [5]. Cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) is frequently found on dogs and other mammals [23, 30]. Dog fleas (C. canis) can, in turn, prey also on cats and foxes [33]. Both cat and dog fleas frequently plague humans [5, 21, 31]. Other species that may also infest people include hen flea (Ceratophyllus gallinae), sparrow flea (Ceratophyllus fringillae), finch flea (Dasypsyllus gallinulae), hedgehog flea (Archaeopsylla erinacei), rabbit flea (Spilopsyllus cunniculi), and European rat flea (Nosopsyllus fasciatus) [5, 7, 21, 50]. On the other hand, human flea (Pulex irritans) frequently infests dogs, goats, and pigs, but also may be found on badgers, foxes and squirrels [9, 22, 25, 30]. Compared to the above species, pigeon flea seems restricted to birds. It is found almost exclusively in pigeons' nests and henhouses [30]. However, as this article demonstrates, the pigeon flea is also capable of attacking humans.

While feeding, fleas inject their saliva into the host's body to prevent the blood from coagulating. The saliva has strong irritating and allergising properties [4, 13, 43]. In experimental conditions, controlled fleabites caused skin reaction in 62% of 269 test persons. An immediate reaction (itch, erythema, and eventually wheal within 20 min after the bite) was observed in 23%, whereas 59% had a late skin reaction (itching, indurated papulae with erythema starting 12-24 h after the bite). Appearance of both immediate and late skin reactions (overlap of both previous groups) was seen in 20% of the test persons [13]. Repeated fleabites may lead to generalised allergic reactions. We have observed this in Mr X, who gradually developed generalised urticaria. Flea allergens may also cause respiratory allergy. Among persons with suspected cat allergy, 9% were in fact allergic to cat fleas, and a further 46% suffered from allergy both to cats and cat fleas [32].

Fleas are much feared as carriers of infectious diseases. In the past, rat and human fleas were vectors of bubonic plague and endemic typhus [4, 24]. Also nowadays, these insects may vector a wide range of infectious and parasitic diseases [1, 2, 4, 29, 46, 49]. Flea infestations remain a considerable health problem to both poor and rich alike, and may even occur in hospital [41]. Summing up the unpleasant, itching skin reactions to fleabites with the well-deserved "bad name" of fleas, one should not be surprised by severe psychological distress which overwhelmed the couple described in this report.

We have documented a rare case of pigeon fleas (Ceratophyllus columbae) invading humans. This report demonstrates that even a single pigeon nest neighbouring human dwellings is sufficient to cause serious and long-lasting problems for the inhabitants.

The authors wish to thank Dr Peter Herger (Lucerne), Marcus Schmidt (Zurich), Gianni Morson (Basel), and Andreas Ochsenbein (Basel) for their kind assistance at various stages of preparing this paper.

For personal use only. © Radoslaw Spiewak.

| Contact Dr. Spiewak | Back to article list | Website's front page |